How to stop End user Licenese Agreement 'EULA' from poping up every time I open a new documrent or use one of office 2003 appplications I reinstalled my office 2003 professional. Every time I open a document or even outlook, the EULA pop up and I must click on accept to go on. It is not a big propblem but anoying.

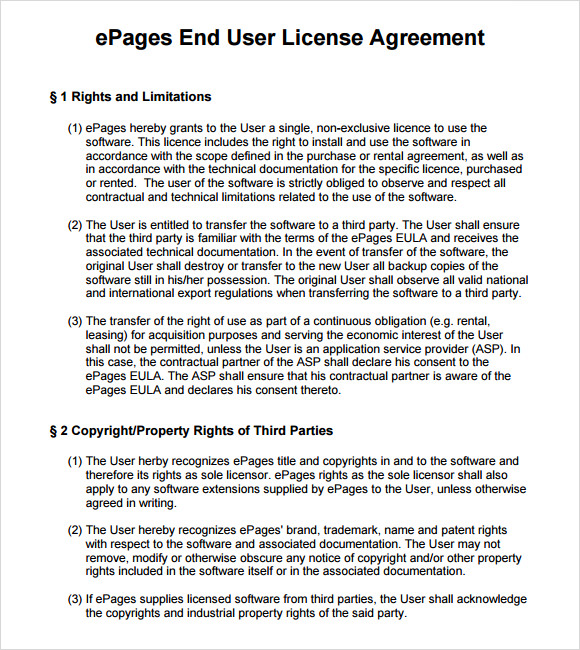

An end-user license agreement (EULA, /ˈjuːlə/) is a legal contract entered into between a software developer or vendor and the user of the software, often where the software has been purchased by the user from an intermediary such as a retailer. A EULA specifies in detail the rights and restrictions which apply to the use of the software.[1]

- End User License Agreement for the Intel® Software Development Products (Version October 2018)-View PDF 512 KB IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT YOUR RIGHTS, OBLIGATIONS AND THE USE OF YOUR DATA – PLEASE READ AND AGREE BEFORE DOWNLOADING, INSTALLING, COPYING OR USING. This Agreement forms a legally binding contract between you, or the.

- Find licenses and terms for Adobe products and services in the following chart. For the terms associated with older versions of these products, visit the archive page. Note – in some Adobe agreements, these terms are referred to as End User License Agreements (EULAs). General Terms of Use.

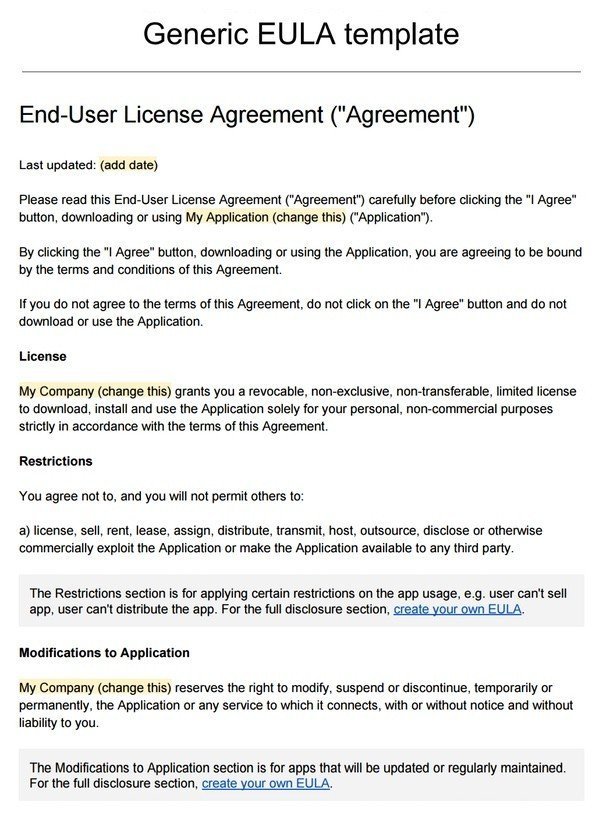

- EULA, which stands for end-user license agreement, is a type of license agreement that details how a product or service can and can’t be used, as well as any other impositions that the manufacturer chooses to place on the user, such as not to share the software with others, etc.

Many form contracts are only contained in digital form, and only presented to a user as a click-through which the user must 'accept'. As the user may not see the agreement until after he or she has already purchased the software, these documents may be contracts of adhesion.

Software companies often make special agreements with large businesses and government entities that include support contracts and specially drafted warranties.

Some end-user license agreements accompany shrink-wrapped software that is presented to a user sometimes on paper or more usually electronically, during the installation procedure. The user has the choice of accepting or rejecting the agreement. The installation of the software is conditional to the user clicking a button labelled 'accept'. See below.

Many EULAs assert extensive liability limitations. Most commonly, an EULA will attempt to hold harmless the software licensor in the event that the software causes damage to the user's computer or data, but some software also proposes limitations on whether the licensor can be held liable for damage that arises through improper use of the software (for example, incorrectly using tax preparation software and incurring penalties as a result). One case upholding such limitations on consequential damages is M.A. Mortenson Co. v. Timberline Software Corp., et al.[citation needed] Some EULAs also claim restrictions on venue and applicable law in the event that a legal dispute arises.

Some copyright owners use EULAs in an effort to circumvent limitations the applicable copyright law places on their copyrights (such as the limitations in sections 107–122 of the United States Copyright Act), or to expand the scope of control over the work into areas for which copyright protection is denied by law (such as attempting to charge for, regulate or prevent private performances of a work beyond a certain number of performances or beyond a certain period of time). Such EULAs are, in essence, efforts to gain control, by contract, over matters upon which copyright law precludes control. [2] This kind of EULAs concurs in aim with DRM and both may be used as alternate methods for widening control over software.

In disputes of this nature in the United States, cases are often appealed and different circuit courts of appeal sometimes disagree about these clauses. This provides an opportunity for the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene, which it has usually done in a scope-limited and cautious manner, providing little in the way of precedent or settled law.[citation needed]

End-user license agreements are usually lengthy, and written in highly specific legal language, making it difficult for the average user to give informed consent.[3] If the company designs the end-user license agreement in a way that intentionally discourages users from reading them, and uses difficult to understand language, many of the users may not be giving informed consent.

Comparison with free software licenses[edit]

A free software license grants users of that software the rights to use for any purpose, modify and redistribute creative works and software, both of which are forbidden by the defaults of copyright, and generally not granted with proprietary software. These licenses typically include a disclaimer of warranty, but this feature is not unique to free software.[4]Copyleft licenses also include a key addition provision that must be followed in order to copy or modify the software, that requires the user to provide source code for the work and to distribute their modifications under the same license (or sometimes a compatible one); thus effectively protecting derivative works from losing the original permissions and being used in proprietary programs.

Unlike EULAs, free software licenses do not work as contractual extensions to existing legislation. No agreement between parties is ever held, because a copyright license is simply a declaration of permissions on something that otherwise would be disallowed by default under copyright law.[2]

Shrink-wrap and click-wrap licenses [edit]

The term shrink-wrap license refers colloquially to any software license agreement which is enclosed within a software package and is inaccessible to the customer until after purchase. Typically, the license agreement is printed on paper included inside the boxed software. It may also be presented to the user on-screen during installation, in which case the license is sometimes referred to as a click-wrap license. The inability of the customer to review the license agreement before purchasing the software has caused such licenses to run afoul of legal challenges in some cases.

Whether shrink-wrap licenses are legally binding differs between jurisdictions, though a majority of jurisdictions hold such licenses to be enforceable. At particular issue is the difference in opinion between two US courts in Klocek v. Gateway and Brower v. Gateway. Both cases involved a shrink-wrapped license document provided by the online vendor of a computer system. The terms of the shrink-wrapped license were not provided at the time of purchase, but were rather included with the shipped product as a printed document. The license required the customer to return the product within a limited time frame if the license was not agreed to. In Brower, New York's state appeals court ruled that the terms of the shrink-wrapped license document were enforceable because the customer's assent was evident by its failure to return the merchandise within the 30 days specified by the document. The U.S. District Court of Kansas in Klocek ruled that the contract of sale was complete at the time of the transaction, and the additional shipped terms contained in a document similar to that in Brower did not constitute a contract, because the customer never agreed to them when the contract of sale was completed.

Further, in ProCD v. Zeidenberg, the license was ruled enforceable because it was necessary for the customer to assent to the terms of the agreement by clicking on an 'I Agree' button in order to install the software. In Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp., however, the licensee was able to download and install the software without first being required to review and positively assent to the terms of the agreement, and so the license was held to be unenforceable.

Click-wrap license agreements refer to website based contract formation (see iLan Systems, Inc. v. Netscout Service Level Corp.). A common example of this occurs where a user must affirmatively assent to license terms of a website, by clicking 'yes' on a pop-up, in order to access website features. This is therefore analogous to shrink-wrap licenses, where a buyer implied agrees to license terms by first removing the software package's shrink-wrap and then utilizing the software itself. In both types of analysis, focus is on the actions of end user and asks whether there is an explicit or implicit acceptance of the additional licensing terms.

Product liability[edit]

Most licenses for software sold at retail disclaim (as far as local laws permit) any warranty on the performance of the software and limit liability for any damages to the purchase price of the software. One well-known case which upheld such a disclaimer is Mortenson v. Timberline.

Patent[edit]

In addition to the implied exhaustion doctrine, the distributor may include patent licenses along with software.

Reverse engineering[edit]

Forms often prohibit users from reverse engineering. This may also serve to make it difficult to develop third-party software which interoperates with the licensed software, thus increasing the value of the publisher's solutions through decreased customer choice. In the United States, EULA provisions can preempt the reverse engineering rights implied by fair use, c.f. Bowers v. Baystate Technologies.

Some licenses[5] purport to prohibit a user's right to release data on the performance of the software, but this has yet to be challenged in court.

Enforceability of EULAs in the United States[edit]

The enforceability of an EULA depends on several factors, one of them being the court in which the case is heard. Some courts that have addressed the validity of the shrinkwrap license agreements have found some EULAs to be invalid, characterizing them as contracts of adhesion, unconscionable, and/or unacceptable pursuant to the U.C.C.—see, for instance, Step-Saver Data Systems, Inc. v. Wyse Technology,[6]Vault Corp. v. Quaid Software Ltd..[7] Other courts have determined that the shrinkwrap license agreement is valid and enforceable: see ProCD, Inc. v. Zeidenberg,[8]Microsoft v. Harmony Computers,[9]Novell v. Network Trade Center,[10] and Ariz. Cartridge Remanufacturers Ass'n v. Lexmark Int'l, Inc.[11] may have some bearing as well. No court has ruled on the validity of EULAs generally; decisions are limited to particular provisions and terms.

The 7th Circuit and 8th Circuit subscribe to the 'licensed and not sold' argument, while most other circuits do not[citation needed]. In addition, the contracts' enforceability depends on whether the state has passed the Uniform Computer Information Transactions Act (UCITA) or Anti-UCITA (UCITA Bomb Shelter) laws. In Anti-UCITA states, the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) has been amended to either specifically define software as a good (thus making it fall under the UCC), or to disallow contracts which specify that the terms of contract are subject to the laws of a state that has passed UCITA.

Recently[when?], publishers have begun to encrypt their software packages to make it impossible for a user to install the software without either agreeing to the license agreement or violating the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and foreign counterparts.[citation needed]

The DMCA specifically provides for reverse engineering of software for interoperability purposes, so there was some controversy as to whether software license agreement clauses which restrict this are enforceable. The 8th Circuit case of Davidson & Associates v. Jung[12] determined that such clauses are enforceable, following the Federal Circuit decision of Baystate v. Bowers.[13]

Criticism[edit]

Jerry Pournelle wrote in 1983, 'I've seen no evidence to show that ... Levitical agreements — full of 'Thou Shalt Nots' — have any effect on piracy'. He gave an example of an EULA that was impossible for a user to comply with, stating 'Come on, fellows. No one expects these agreements to be kept'. Noting that in practice many companies were more generous to their customers than their EULAs required, Pournelle wondered 'Why, then, do they insist on making their customers sign 'agreements' that the customer has no intention of keeping, and which the company knows won't be kept? ... Must we continue making hypocrites out of both publishers and customers?'[14]

One common criticism of end-user license agreements is that they are often far too lengthy for users to devote the time to thoroughly read them. In March 2012, the PayPal end-user license agreement was 36,275 words long[15] and in May 2011 the iTunes agreement was 56 pages long.[16] News sources reporting these findings asserted that the vast majority of users do not read the documents because of their length.

Several companies have parodied this belief that users do not read the end-user-license agreements by adding unusual clauses, knowing that few users will ever read them. As an April Fool's Day joke, Gamestation added a clause stating that users who placed an order on April 1, 2010 agreed to irrevocably give their soul to the company, which 7,500 users agreed to. Although there was a checkbox to exempt out of the 'immortal soul' clause, few users checked it and thus Gamestation concluded that 88% of their users did not read the agreement.[17] The program PC Pitstop included a clause in their end-user license agreement stating that anybody who read the clause and contacted the company would receive a monetary reward, but it took four months and over 3,000 software downloads before anybody collected it.[18] During the installation of version 4 of the Advanced Query Tool the installer measured the elapsed time between the appearance and the acceptance of the end-user license agreements to calculate the average reading speed. If the agreements were accepted fast enough a dialog window “congratulated” the users to their absurdly high reading speed of several hundred words per second.[19]South Park parodied this in the episode 'HumancentiPad', where Kyle had neglected to read the terms of service for his last iTunes update and therefore inadvertently agreed to have Apple employees experiment upon him.[20]

End-user license agreements have also been criticized for containing terms that impose onerous obligations on consumers. For example, Clickwrapped, a service that rates consumer companies according to how well they respect the rights of users, reports that they increasingly include a term that prevents a user from suing the company in court.[21]

In a recent article published by Kevin Litman-Navarro for The New York Times, titled We Read 150 Privacy Policies. They Were an Incomprehensible Disaster,[22] the complexity of 150 terms from popular sites like Facebook, Airbnb, etc. were analyzed and comprehended. As a result, for example, the majority of licenses require college or higher-level degrees: 'To be successful in college, people need to understand texts with a score of 1300. People in the professions, like doctors and lawyers, should be able to understand materials with scores of 1440, while ninth graders should understand texts that score above 1050 to be on track for college or a career by the time they graduate. Many privacy policies exceed these standards.'[22]

See also[edit]

- Glossary of legal terms in technology

References[edit]

- ^Linux Foundation, EULA Definition, published 28 February 2006, accessed 10 August 2019

- ^ abEben Moglen (10 September 2001). 'Enforcing the GNU GPL'. gnu.org. Free Software Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^Bashir, M., Hayes, C., Lambert, A. D., & Kesan, J. P. (2015). Online privacy and informed consent: The dilemma of information asymmetry. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 52(1), 1-10. doi:10.1002/pra2.2015.145052010043

- ^Con Zymaris (5 May 2003). 'A Comparison of the GPL and the Microsoft EULA'(PDF): 3, 12–16. Archived from the original(PDF) on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2013.Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^Examples include Microsoft .NET Framework redistributable EULA

- ^939 F.2d 91 (3rd Cir., 1991)

- ^847 F.2d 255 (5th Cir., 1988)

- ^86 F.3d 1447 (7th Cir., 1996)

- ^846 F. Supp. 208 (E.D.N.Y., 1994)

- ^25 F.Supp.2d 1218 (D. Utah, 1997)

- ^421 F.3d 981 (9th Cir., 2005)

- ^422 F. 3d 630 (8th Cir., 2005)

- ^302 F.3d 1334 (Fed. Cir., 2002)

- ^Pournelle, Jerry (June 1983). 'Zenith Z-100, Epson QX-10, Software Licensing, and the Software Piracy Problem'. BYTE. p. 411. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^Heathen (23 March 2012). 'No One Reads the 'Terms And Conditions' and Here's Why'. 102.5 KISSFM. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^Pidaparthy, Umika (May 6, 2011). 'What you should know about iTunes' 56-page legal terms'. CNN. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^'7,500 Online Shoppers Unknowingly Sold Their Souls'. FoxNews.com. April 15, 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^Magid, Larry. 'PC Pitstop'. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^Willmott, Don. 'Backspace (v22n08)'. PCMag.com. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^O'Grady, Jason D. 'South Park parodies iTunes terms and conditions'. ZDNet. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^Jamillah Knowles. Clickwrapped report tells you which sites claim ownership of your content, and you’ll be surprised. TheNextWeb. August 21, 2012. Accessed July 29, 2013.

- ^ abLitman-Navarro, Kevin (2019-06-12). 'Opinion | We Read 150 Privacy Policies. They Were an Incomprehensible Disaster'. The New York Times. ISSN0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-06-23.

External links[edit]

February 2005

By Annalee Newitz

We've all seen them – windows that pop up before you install a new piece of software, full of legalese. To complete the install, you have to scroll through 60 screens of dense text and then click an 'I Agree' button. Sometimes you don't even have to scroll through to click the button. Other times, there is no button because merely opening your new gadget means that you've 'agreed' to the chunk of legalese.

They're called End User License Agreements, or EULAs. Sometimes referred to as 'shrinkwrap' or 'click-through' agreements, they are efforts to bind consumers legally to a number of strict terms – and yet you never sign your name. Frequently, you aren't even able to see a EULA until after you've purchased the item it covers.

Although there has been some controversy over whether these agreements are enforceable, several courts have upheld their legitimacy.1 These days, EULAs are ubiquitous in software and consumer electronics -- millions of people are clicking buttons that purport to bind them to agreements that they never read and that often run contrary to federal and state laws. These dubious 'contracts' are, in theory, one-on-one agreements between manufacturers and each of their customers. Yet because almost every computer user in the world has been subjected to the same take-it-or-leave-it terms at one time or another, EULAs are more like legal mandates than consumer choices. They are, in effect, changing laws without going through any kind of legislative process. And the results are dangerous for consumers and innovators alike.

It's time that consumers understood what happens when they click 'I Agree.' They may be inviting vendors to snoop on their computers, or allowing companies to prevent them from publicly criticizing the product they've bought. They also click away their right to customize or even repair their devices. This is a guide for the 'user' in EULA, the person who stands to lose the most by allowing companies to assert that these click-through agreements count as binding contracts.

Common EULA Terms That Harm Consumers

There are countless terms written into EULAs that could potentially harm consumers, or that may be downright unlawful. Here we offer an overview of some of the most common of these terms, and include sample legal language to help consumers become more EULA-savvy.

1. 'Do not criticize this product publicly.'

Hidden within the terms of many EULAs are often serious demands asking consumers to sign away fundamental rights. Many agreements on database and middleware programs forbid the consumer from comparing his or her product with another and publicly criticizing the product. This obviously curtails free speech2, and makes it more difficult for consumers to get accurate information about what they're buying by inhibiting professional watchdog groups like Consumer Reports from conducting independent reviews.

How does this happen? People click 'I Agree' to EULAs that attempt to forbid 'benchmarking' -- the process of measuring the performance of hardware or software in a controlled and defined environment. McAfee (a.k.a. Network Associates) was sanctioned in 2003 for including in its EULA the condition, 'The customer shall not disclose the results of any benchmark test to any third party without Network Associates' prior written approval.'3 And yet anti-benchmarking and anti-public criticism terms exist in many EULAs to this day.

According to terms in several Microsoft EULAs, including those for MS XML and the SQL Server, you 'may not without Microsoft's prior written approval disclose to any third party the results of any benchmark test.'4 Similar terms appear in EULAs for countless other applications, including one for the VMware Desktop Software, which reads, 'You may not disclose the results of any benchmark test of the Software to any third party without VMware's prior written approval.5

Not only do terms like these prevent people from engaging in free speech, but they also undermine fair competition in the marketplace. Microsoft, for example, can publish benchmarks comparing its database products to open source alternatives. And yet their EULA terms suggest that the authors of open source products cannot publish the results of their own comparisons. What this means is that the only information consumers have access to is extremely one-sided and potentially biased.

2. 'Using this product means you will be monitored.'

Many products come with EULAs with terms that force users to agree to automatic updates – usually by having the computer or networked device contact a third party without notifying the consumer, thus potentially compromising privacy and security.6

Section 2.1 of the Windows XP Home Edition EULA7 includes a Digital Rights Management (DRM) Notice, which contains the following terms:

'If the DRM Software's security has been compromised, owners of Secure Content ('Secure Content Owners') may request that Microsoft revoke the DRM Software's right to copy, display and/or play Secure Content. Revocation does not alter the DRM Software's ability to play unprotected content. A list of revoked DRM Software is sent to your computer whenever you download a license for Secure Content from the Internet. You therefore agree that Microsoft may, in conjunction with such license, also download revocation lists onto your computer on behalf of Secure Content Owners.'

Note that by clicking through the EULA for Windows XP, you are also agreeing to let Microsoft download software onto your computer on behalf of third parties, identified only as the 'Secure Content Owners.'

The Windows license, however, is less invasive than the terms of Pinnacle's Studio 9 movie-making software. See the DRM-related provisions in Section 6 of the Pinnacle EULA8 :

'You acknowledge and agree that in order to protect the integrity of certain third party content, Pinnacle and/or its licensors may provide for Software security related updates that will be automatically downloaded and installed on your computer. Such security related updates may impair the Software (and any other software on your computer which specifically depends on the Software) including disabling your ability to copy and/or play ‘secure' content, i.e. content protected by digital rights management.'

Clicking through this EULA appears to allow Pinnacle to install software automatically from third parties onto your computer – software which the vendor admits may 'impair' the program ('the Software') you have just purchased, as well as 'any other software on your computer which specifically depends on the Software.'

Another disturbing 'automatic update' style term appears in McAfee's EULA – it's an automatic subscription renewal clause which says that the company might just charge your credit card an 'automatic' fee when your subscription runs out. Agreeing to this EULA seems to mean you may be a McAfee subscriber forever: 'Upon expiration of your subscription to the Software, the Company may automatically renew your subscription to the Software at the then prevailing price using credit card information you have previously provided.'9

3. 'Do not reverse-engineer this product.'

Some EULA terms harm people who want to customize their technology, as well as inventors who want to create new products that work with the technology they've bought. 'Reverse-engineering,' which is often forbidden in EULAs, is a term for taking a machine or piece of software apart in order to see how it works. This kind of tinkering is explicitly permitted by federal law – it is considered a 'fair use' of a copyrighted item. Courts have held that the fair use provisions of the US Copyright Act allow for reverse-engineering of software when the purpose is to create a non-infringing interoperable program.10

And yet, most EULAs take away the rights granted by this federal sanction. This has far-reaching implications. Without reverse-engineering, consumers are unable to tailor software and devices to their liking – they can't create a custom version of a gadget so that it can work with other electronics they own. They can't turn off features that they don't like. Even worse, EULAs that forbid reverse-engineering also threaten healthy competition in the marketplace by forbidding people from creating innovative new products that enhance older ones. Essentially, these terms create consumer lock-in – you must use the product as-is, without any modifications, and no one else may develop add-ons to the product that you might enjoy.

Consider this EULA from Intel, which states simply, 'You may not reverse engineer, decompile, or disassemble the Software.'11 Napster users must click through a similar EULA that advises they are not to 'modify, alter, decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer or emulate the functionality, reverse compile or otherwise reduce to human readable form, or create derivative works of the Software without the prior written consent of Napster or its licensors, as applicable.'12 These kinds of anti-reverse-engineering clauses – which are incredibly common – seek to undermine the lawfulness of many types of reverse-engineering,13 and thus wind up discouraging innovation, creativity, and exploration.

Section 4 of the Windows XP Home Edition EULA14 manages to acknowledge federal copyright law while nevertheless trying to impress upon consumers that they really shouldn't reverse-engineer anyway:

'LIMITATIONS ON REVERSE ENGINEERING, DECOMPILATION, AND DISASSEMBLY. You may not reverse engineer, decompile, or disassemble the Software, except and only to the extent that such activity is expressly permitted by applicable law notwithstanding this limitation.'

Here, Microsoft has expressly nodded to fair use protections for reverse-engineering, but unless those reading the EULA are familiar with how 'such activity' is 'permitted by applicable law,' they are likely to get the impression that most kinds of tinkering are unlawful.

4. 'Do not use this product with other vendor's products.'

Vendors use EULAs to make consumers agree that they won't use products that evaluate the performance of the software they've bought, or that can be used to uninstall all or part of the program. Essentially, clicking 'I Agree' to such a EULA means that you're not supposed to reconfigure your computer to touch or remove the software you've just installed. These kinds of EULA terms have become popular lately because many vendors support free versions of their products by packaging them with third-party programs that serve ads or gather information about consumer habits for marketing companies. If users uninstalled such ride-along programs at will, the vendors might lose revenue. For example, Claria (formerly Gator) is a company that delivers pop-up ads and pays to have its GAIN software bundled in free versions of popular file-sharing program Kazaa. The Claria EULA warns:

You agree that you will not use, or encourage others to use, any unauthorized means for the removal of the GAIN AdServer, or any GAIN-Supported Software from a computer . . . Any use of a packet sniffer or other device to intercept or access communications between GP and the GAIN AdServer is strictly prohibited.15

In other words, users are threatened with a suit if they use 'unauthorized' programs to remove Claria's product.16 Also, users are told not to use a common network diagnostic tool, the packet sniffer, to figure out what kinds of actions the GAIN AdServer is taking on the network, even if their intent is to fix a problem with their computer or their network. Worst of all, the EULA actually claims to prohibit the user from 'encouraging' others to use removal programs, meaning that according to Claria, even suggesting to a friend that use of such a program might improve their computer performance is illegal.

Kazaa echoes these terms when it warns users that they can't use products that might 'monitor or interfere' with the operations of Kazaa's software:

You may not use, test or otherwise utilize the Software in any manner for purposes of developing or implementing any method or application that is intended to monitor or interfere with the functioning of the Software.17

What this means is that you can't run any programs (like packet sniffers) that analyze the performance of Kazaa, evaluate what it's doing, or change the way it operates on your computer. Kazaa reserves the right to tell you what you can and cannot do with the program on your own machine.

5. 'By signing this contract, you also agree to every change in future versions of it.

Oh yes, and EULAs are subject to change without notice.'

In its Service Agreement for iTunes, Apple informs consumers:

Apple reserves the right, at any time and from time to time, to update, revise, supplement, and otherwise modify this Agreement and to impose new or additional rules, policies, terms, or conditions on your use of the Service. Such updates, revisions, supplements, modifications, and additional rules, policies, terms, and conditions (collectively referred to in this Agreement as 'Additional Terms') will be effective immediately and incorporated into this Agreement. Your continued use of the iTunes Music Store following will be deemed to constitute your acceptance of any and all such Additional Terms. All Additional Terms are hereby incorporated into this Agreement by this reference.18

Put simply, this means that when you install iTunes, you are not only agreeing to all the onerous terms in the box, but you are also agreeing to future terms that may appear in the iTunes Terms of Service months or years from now. These terms are subject to change without notice, and you don't even get a chance to click through this future 'contract' and agree. Mere 'continued use of the iTunes Music Store' constitutes your agreement to contractual terms that you may not be aware exist. These kinds of terms are ubiquitous in EULAs and in Terms of Service for countless products.

Even the Mirar Toolbar, an advertising program similar to Gator, has these terms in its EULA. Agreeing to the EULA, which 'will be changed without further notice,' covers any future changes in terms:

Installation and use of this software signifies acceptance of the EULA inclusive of any future updates. 19

6. 'We are not responsible if this product messes up your computer.'

The disclaimer of liability for faulty software is perhaps the most important function of a EULA from the manufacturer's perspective. And it's bad news for the consumer. This term purports to supplant traditional consumer protection and products liability law. Clicking yes on EULAs containing this common clause means that the consumer cannot file class-action lawsuits against the vendor for faulty products, or for products that do not do all the things that the company advertised they would.

This kind of agreement would seem absurd if applied to other kinds of consumer electronics. If you buy a microwave, there's a large body of common law and statute that gives you rights against its manufacturer if it blows up, burns you, or singes your countertop. You can hold the manufacturer liable for 'foreseeable' malfunctions or injuries, or for the product's failure to work as advertised. But if you buy a piece of software, the EULA often disclaims all that prior law, without putting alternate consumer protections in its place.

Here is a typical clause, from the Windows XP EULA:

Except for any refund elected by Microsoft, YOU ARE NOT ENTITLED TO ANY DAMAGES, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, if the Software does not meet Microsoft's Limited Warranty, and, to the maximum extent allowed by applicable law, even if any remedy fails of its essential purpose.20

While the Limited Warranty itself only lasts for 90 days, the language above purports to shield Microsoft even if a crash costs you a massive amount of data during the Warranty period. But at least you only have to pay shipping for the new version of XP:

You will receive the remedy elected by Microsoft without charge, except that you are responsible for any expenses you may incur (e.g. cost of shipping the Software to Microsoft).

A warranty disclaimer is generally found in most EULAs despite the fact that it runs counter to the very basis of products liability law.

The Trouble with EULAs

EULAs started as a way for companies to limit warranties on goods and disclaim liability. These documents became widespread in the mid-1980s, when the growing popularity of software programs led vendors to seek new ways of limiting people's ability to copy their products. Also, many early EULAs prohibited reverse-engineering to prevent people from creating knockoff products that they would sell competitively. Eventually, the EULA became the choke-collar that it is today, limiting people's ability to talk about products, take them apart, and even remove them from their computers.

In a 2004 case, Blizzard Entertainment and Vivendi Universal Games sued the makers of a free software program called BnetD because people could use it to play Blizzard games online without Blizzard's approval. The game company argued that BnetD's developers had violated several terms in the Blizzard EULA because they reverse-engineered a protocol in order to make the BnetD server interoperate with Blizzard videogames.21

EULAs make millions of consumers into potential victims of frivolous lawsuits. They also lead to problems with interoperability, since reverse-engineering to develop those interoperable products is often prohibited. In addition, they allow consumers' security to be compromised.

Many vendors won't let consumers look at the EULA before purchasing an item,22 which means people can't make informed decisions about what they're buying. Sometimes companies make their EULA so hard to find and difficult to read that even conscientious consumers feel at a loss to understand the terms to which they've agreed.

Fight the EULA

There is hope. Consumers, lawmakers, and activists can take action to reform EULAs. Like other consumer rights struggles, such as the push to make food companies label their products, fighting EULAs will require grassroots organizing and legislative change. As the public learns more about how EULAs deprive them of basic rights they take for granted, challenges to these anti-consumer 'agreements' are likely to become more common.

Many attorneys and policymakers have suggested that federal consumer protection and copyright laws ought to prohibit or preempt some of the more egregious terms set forth in EULAs. EFF lawyers defending the developers of BnetD raised this point when they argued that federal copyright laws expressly permit reverse-engineering.23

Consumers can also use state consumer protection laws to demonstrate that they are being harmed by having to agree to terms in EULAs that limit freedom of expression and entrepreneurial initiative. In 2003, a California woman filed a class-action suit against Microsoft, Symantec, and several retail outlets, claiming unfair business practices because consumers can't read EULAs before buying a product, and can't return them if they decide they don't like the EULA's terms. The case was settled when the named vendors and retailers agreed to make their EULAs available for people to read before purchase.24

Consumer activism will be crucial to reforming EULAs. Obviously, a first step is to educate consumers about the potential dangers of clicking through a EULA without reading it carefully first. The readers of Ed Foster's GripeLog, a blog partly devoted to analyzing EULAs, have formed an active community of EULA busters whose public complaints have helped remove some of the most damaging terms from certain EULAs.25

Boycotts, combined with write-in campaigns, have proven effective in the past. In 1999, when Yahoo purchased the free website-hosting company Geocities, Yahoo changed the usage agreement for Geocities. The new agreement said that all content on Geocities would belong exclusively to Yahoo.26 After a well-orchestrated boycott and publicity campaign run by Geocities users, Yahoo changed the terms and restored ownership of website content to Geocities' users.27

Organizational efforts like these demonstrate that companies can and do respond to public pressure to reform their EULAs. Bringing together the organizational potential of consumer activist groups, blogs, and online communities with legal and legislative challenges, consumers can regain the rights they lost the first time they clicked 'I Agree.'

The EULA Strikes Back

Today's high-tech products are often built with networking capabilities, and as a result we are seeing the rise another species of clickwrap contract: the Terms of Service (TOS) agreement. Like EULAs, TOS attempt to bind online users without a signature. Sometimes they have a click-through component, and sometimes online service providers bury them in a tiny link at the bottom of a website or portal. TOS agreements attempt to govern the way consumers use online services such as webmail, social networking websites, game servers, wireless hotspots, chat software, and more. Many consumer electronics products, such as Microsoft's Xbox, can be used both on- and offline. Such products arguably subject their users to the terms of both EULAs and TOS agreements.

Many terms are shared between EULAs and TOS agreements. But typical TOS agreements also include terms that forbid vaguely defined forms of behavior and communication. Some state that all communications via an online service will be monitored. As TOS agreements become more common, we are likely to see their reach extend off the network and onto consumers' private machines. It's very likely that we will begin to see more and more TOS agreements that forbid consumers from using products to discuss certain socially stigmatized topics, or that assign to the vendor ownership of all consumer data stored with its service. And because many online services also install software or store data on consumers' computers, TOS agreements may claim to govern user activity on private computers, too.

Many people treat EULAs with the same reverence they do the tags on mattresses that say, 'Do not remove this tag under penalty of law.' They scoff at the idea that anyone could enforce such a bizarre rule. Increasingly, however, we are seeing consumers and software developers threatened with lawsuits for engaging in the digital equivalent of ripping tags off a mattress.

With consumer activism, as well as actions that push our legislatures and courts to change consumer protection laws, we can prevent corporations from taking away our rights one mouse click at a time.

If you have been harmed by a EULA, or threatened with legal action because of one, EFF wants to hear your story. E-mail us at EULAharm@eff.org.

For Further Reading

Online Resources:

Americans for Fair Electronic Commerce Transactions (AFFECT), an organization that opposes unfair clickwrap terms and organizes consumer and legal campaigns.

http://www.ucita.com

Ed Foster's GripeLog weblog has a section devoted to consumer rights and EULAs:

http://www.gripe2ed.com/scoop/section/Eula

The Bureau of Consumer Protection, a division of the FTC that enforces consumer protection laws enacted by Congress:

http://www.ftc.gov/ftc/consumer/home.html

'PC Invaders,' a 2002 article from C|Net on EULAs from a consumer rights perspective:

http://news.com.com/2009-1023-885144.html

'Software User's Rights' by DJ Bernstein:

http://cr.yp.to/softwarelaw.html

Law Articles:

David Nimmer, Metamorphosis of Contract into Expand, 87 Cal. L. Rev. 17 (1999)

http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/openlaw/DVD/research/metamorphosis.html

Mark Lemley, Beyond Preemption, 87 Calif. L. Rev. 111 (1999)

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=98655

Lydia Loren, Slaying the Leather-Winged Demons in the Night, 30 Ohio Northern University Law Review (2004)

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=582402

David A Rice, Copyright and Contract: Preemption After Bowers v. Baystate, 9 Roger Williams L. Rev. 595 (2004)

Robert W.Gomulkiewicz, The License is the Product: Comments on the Promise of Article 2B for Software Information Licensing, 13 Berkeley Tech., L.J. 891 (1998)

David McGowan, Free Contracting, Fair Competition, and Article 2B: Some Reflections on Federal Competition Policy, Information Transactions, and 'Aggressive Neutrality,' 13 Berkeley Tech., L.J. 1173 (1998)

Michael J. Madison, Legal-Ware: Contract and Copyright in the Digital Age, 67 Fordham L. Rev. 1025 (1998)

Proceedings from a 1998 conference at Berkeley's Boalt Law School called 'Intellectual Property and Contract Law in the Information Age.'

http://www.law.berkeley.edu/institutes/bclt/events/ucc2b/index.html

Footnotes

1 See, for example, ProCD, Inc. v. Zeidenberg, a case challenging the validity of clickwrap contracts in which the Seventh Circuit court of appeals decided in 1996 that contract terms displayed on a computer screen after purchase did constitute a valid contract. Read the ruling at http://laws.lp.findlaw.com/7th/961139.html. Other court cases about the enforceability of EULAs often cite ProCD.

2

Lydia Pallas Loren makes a persuasive argument about EULA's anti-benchmarking and public criticism terms curtailing free speech in her article 'Slaying the Leather-Winged Demons in the Night: Reforming Copyright Owner Contracting with Clickwrap Misuse' in Ohio Northern University Law Review (2004). View the paper at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=582402.

3 In People of the State of New York v. Network Associates, the chief of Attorney General Eliot Spitzer’s Internet Bureau persuaded the Court to prevent Network Associates from selling software under conditions that prohibited consumers from disclosing the results of benchmark tests or from publishing reviews of Network Associates' products without permission.

4http://www.gripe2ed.com/scoop/story/2003/12/15/01012/835 and http://www.tbray.org/ongoing/When/200x/2003/06/10/BenchmarkFreeSpeech

5 See http://www.vmware.com/download/ws4_eula.html

6 For an interesting analysis of the privacy and security issues around automatic update terms in EULAs, see 'Check the Fine Print' http://www.infoworld.com/articles/op/xml/02/02/11/020211opfoster.html.

7 See http://www.microsoft.com/windowsxp/home/eula.mspx.

8 See http://www.pinnaclesys.com/WebVideo/Studio%20version%209/English(US)/doc/Studio_e.pdf.

9 See http://us.mcafee.com/root/aboutUs.asp?id=eula.

10 Sega Enterprises, Ltd. v. Accolade, Inc., 977 F.2d 1510 (9th Cir. 1992); Atari Games Corp. v. Nintendo of America, Inc., 975 F.2d 832.

11 See http://www.intel.com/design/network/drivers/sla_ec.htm?url=

12 See http://www.napster.com/eula.html

13 §1201 of the Copyright Act allows anyone who lawfully obtains a copy of a computer program to reverse-engineer the program to determine the functional components of the code necessary to make compatible programs. The right to reverse-engineer includes the ability to circumvent technological protections that stop users from accessing these functional elements. See http://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap12.html#1201.

14 See http://www.microsoft.com/windowsxp/home/eula.mspx.

15 See Claria license at http://www.benedelman.org/spyware/claria-license/license-112504.html. Ben Edelman also has a thorough analysis of the license at http://www.benedelman.org/news/112904-1.html.

16

It's also worth noting that this kind of license term sets a trap for anti-spyware vendors like LavaSoft, since Claria could go to court and claim that LavaSoft's tools intentionally interfere with GAIN.

Eula End User License Agreement

17 Section 3.4 from the Kazaa EULA http://guide.kazaa.com/eula.htm.

Eula End User License Agreement 中文

18 See section 20, http://www.apple.com/support/itunes/legal/terms.html.

19 See http://www.kephyr.com/spywarescanner/library/mirartoolbar.winnb41/eula20040319.phtml.

20 See http://www.microsoft.com/windowsxp/home/eula.mspx.

21 For more information about this case, see 'Blizzard v. BnetD' http://www.eff.org/IP/Emulation/Blizzard_v_bnetd/

22 See http://www.gripe2ed.com/scoop/story/2005/1/11/1939/04481 for Ed Foster's discussion of how several vendors refused to allow consumers access to their EULAs until after purchase. A class-action lawsuit changed this practice in some cases, but not all.

23 See the Appellant's Brief in the case: http://www.eff.org/IP/Emulation/Blizzard_v_bnetd/20050112_Opening_Brief_of_Defendants.pdf

24 See 'Lawsuit Challenges Software Licensing' http://news.com.com/2100-1001-983988.html?tag=fd_top or read the complaint at http://www.techfirm.com/Baker-Final.pdf

25 You can find Ed Foster's EULA-related blog entries at http://www.gripe2ed.com/scoop/section/Eula. Foster reports that reader outcry was responsible for Hilton.com removing several privacy-unfriendly terms from its website usage agreement.

26 Users of social networking site Orkut.com are forced to agree to similar terms of use as of 2004. One section of these terms reads, 'By submitting, posting or displaying any Materials on or through the orkut.com service, you automatically grant to us a worldwide, non-exclusive, sublicenseable, transferable, royalty-free, perpetual, irrevocable right to copy, distribute, create derivative works of, publicly perform and display such Materials.' See http://www.orkut.com/terms.aspx.

27http://www.wired.com/news/technology/0,1282,20472,00.html and 'Yahoo Relents on Geocities Terms' http://news.com.com/2100-1023-227916.html?legacy=cnet.